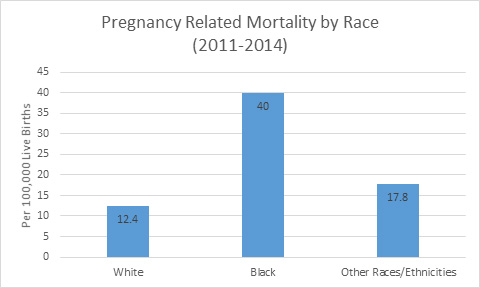

Our health system is failing women, with research indicating that women in the United States (U.S.) are more likely to die from childbirth or other pregnancy-related complications when compared to women in other developed countries. In fact, the U.S., Afghanistan, and Sudan are the only countries in the world where the maternal mortality rate is on the rise. This troubling trend of pregnancy-related mortality has seen a steady increase in the United States, rising by 20 percent between 2000 and 2013. Black women and their babies are experiencing this at disproportionate rates. The crisis of maternal and infant health outcomes for black women and their babies is a clear manifestation of centuries of structural and institutional racism.

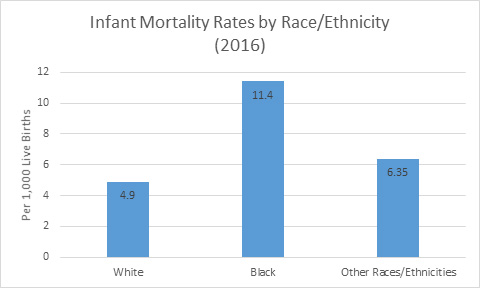

Data show the persistence of clear racial disparities in maternal and infant health. When controlling for factors such as physical health, access to prenatal care, income level, education, and socio-economic status, black women are still three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related death than their non-Hispanic white counterparts. Most troubling is that of these deaths, research indicates that approximately half are preventable with the two leading causes being from hemorrhage and hypertension. The chronic exposure to racism that black women experience also has implications on the health of their infants and children—because parent and child health is inextricably linked. As a result, not only are black women at higher risk of experiencing poor maternal health outcomes, their young children are also at greater health risk of experiencing poor birth outcomes such as pre-term birth and low birth weight—potential causes of infant mortality.

Black women are 49 percent more likely to deliver prematurely than white women, with their babies being twice as likely as white babies to die before their first birthday. Advanced education and higher income provide little reprieve, as babies born to well educated, middle-class black mothers are more likely to die before their first birthday than babies born to poor white mothers with less than a high school education.

Recently, much needed attention is being paid to this issue by journalists, policymakers, advocates, and healthcare providers. However, to make meaningful progress moving forward, a lot of work is left to be done. There have been some encouraging legislative efforts, a bill introduced by Sen. Harris (D-CA), the Maternal Care Access and Reducing Emergencies (CARE) Act, focuses on implicit biases black women experience during pre- and post-natal care. Reps. Lauren Underwood (D-Ill.) and Alma Adams (D-N.C.) announced the creation of a Black Maternal Health Caucus—aiming to elevate black maternal health as a national priority and explore and advocate for effective, evidence-based, culturally competent policies and best practices for improving black maternal health and healthcare.

While the efforts underway are important, for meaningful change to take hold, reproductive health advocates, health care providers, and policymakers must work together to develop solutions. These solutions will only be successful if they respond to the needs of the women most affected by this issue—black women. At CSSP, we work to achieve a racially, economically, and socially just society in which all children and families thrive, in part, through the promotion of public policies grounded in equity. With this frame in mind, we recommend the following considerations be taken into account in aiming to reverse this troubling trend:

- Expand access to healthcare coverage for poor and low-income women through the Medicaid expansion. This includes ensuring continuity of coverage for women during the post-natal period (up to a year after giving birth).

- Advance preventative measures such as comprehensive reproductive health education and health screenings through the utilization of resources provided by Title X family planning programs.

- Continue to build research on maternal mortality and morbidity by prioritizing the collection and dissemination of data that can be disaggregated by race and ethnicity.

- Mitigate racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes through the implementation of culturally competent and culturally responsive policies that provide for training to address implicit bias.

Women are dying at an unacceptable rate during childbirth in the U.S. Good prenatal healthcare is one of the most important aspects of reducing the risk associated with pregnancy and birth. Receiving effective care—both pre- and post-natal—is unfortunately, not guaranteed for women in our country. This is especially the case for black women, who are not receiving the pre- and post-natal care that they should be able to expect—resulting in devastating consequences for themselves, their babies, their families, and their communities. We all have a role to play in stemming the tide of this preventable crisis. By making targeted investments in positive maternal health outcomes—particularly for those experiencing the direst outcomes—we are in turn making an investment in the well-being of entire families and all of our communities.

Rhiannon Reeves is a Policy Analyst at CSSP.