Equity at the Center of Implementation

December 10, 2019

by

In 2017, when the Annie E. Casey Foundation began developing a strategy for incorporating implementation science into its work, Casey’s leadership knew that equity and inclusion—already core principles in the organization’s mission to achieve results for kids, families, and communities—had to be at the center. But the search for models of achieving equity through implementation came up empty. There was no blueprint for success.

Casey did have ongoing partnerships with the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN), a leading institution in the field of implementation science that was similarly seeking ways to incorporate racial and ethnic equity into its implementation practice, and the William T. Grant Foundation, a prominent proponent of helping child welfare agencies and others use research and evidence to serve children and families. Together, representatives of these three organizations began to develop a concept of equitable implementation.

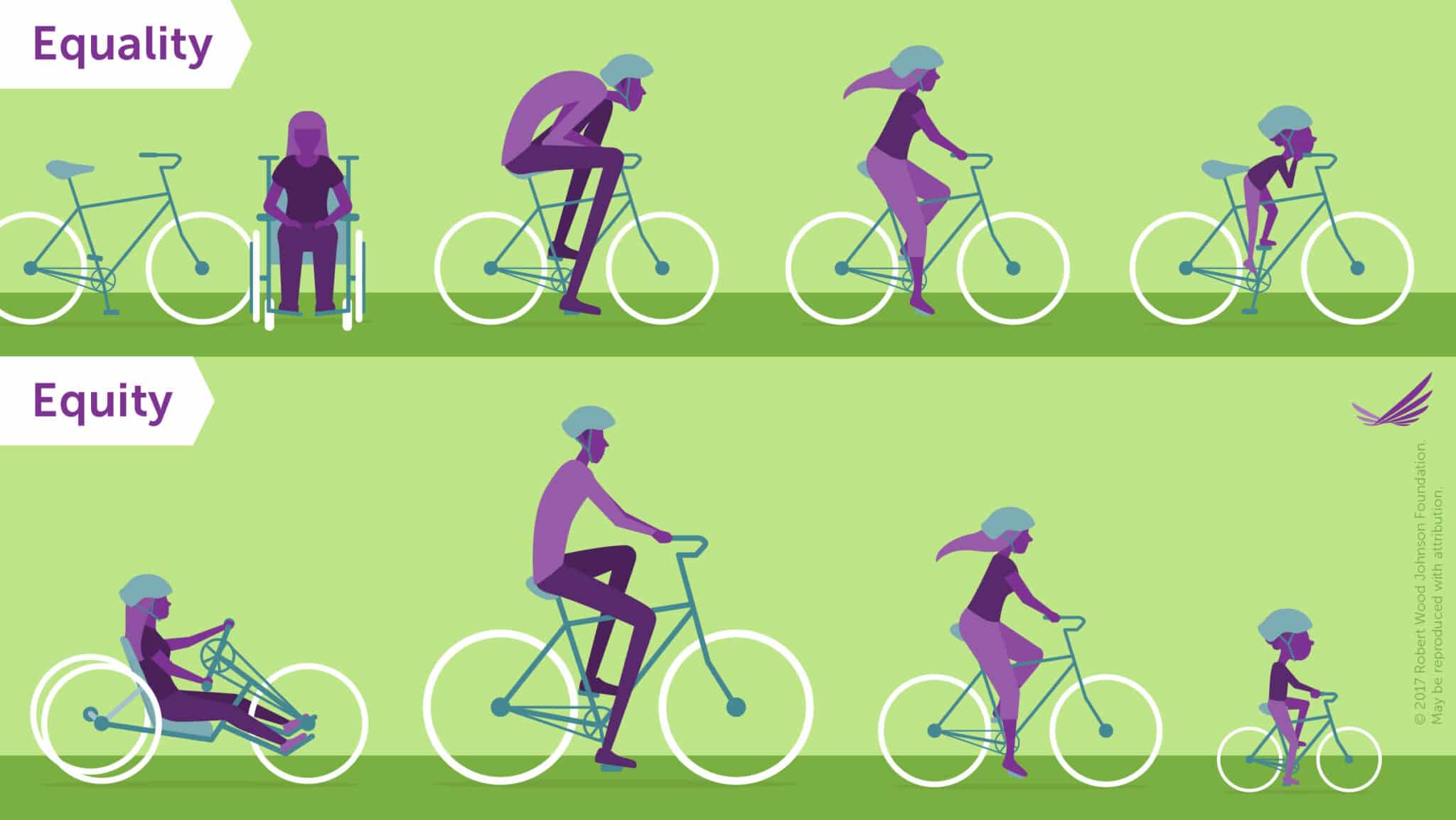

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on RWJF.org

What is equitable implementation?

Equitable implementation occurs when strong equity components—including explicit attention to the culture, history, values, and needs of the community—are integrated into the principles and tools of implementation science. The goal is to facilitate high-quality implementation of effective programs for a specific community or group of communities. Equitable implementation is a strong complement to CSSP’s ongoing work to put equity at the center of knowledge development

The why is simple: We’re never going to achieve equitable outcomes unless racial and ethnic equity and inclusion are integrated into implementation research and practice. This means changing the way we approach implementation.

Equitable implementation puts equity at the center of knowledge use. Principles of equitable implementation can serve as a guide for asking questions, developing research designs, analyzing and synthesizing various forms of knowledge, and selecting implementation strategies in ways that support culturally responsive implementation.

Equitable implementation works to addresses cultural, systemic, and structural norms that privilege some groups over others by:

- sharing power so that the voices of those who develop a practice, those who use and validate a practice, and those who experience a practice are equal;

- shedding the solo hero model in favor of teaming structures that distribute power, responsibility, and accountability;

- abandoning the belief that there is a single right answer or approach and embracing the complexity and the need to be flexible; and,

- accepting discomfort and emotion as part of the process of ensuring that cultural knowledge and experience are incorporated instead of ignored or devalued.

To deepen and advance the conversation, our organizations co-hosted a breakfast discussion at AcademyHealth’s December 2018 Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health. More than 20 implementation scientists gathered to talk about what is needed to integrate equity into implementation science and generated recommendations for incorporating equity in all aspects of research infrastructure and practice.

Since that conversation, we have continued to identify the concrete actions that different actors can take to adapt an implementation structure and practice to ensure a true partnership in creating interventions that balance fidelity to core, evidence-based components with culturally appropriate adaptations that reflect the values, history, and experiences of the setting. Funders, researchers, practitioners, and community members must be equal partners. The actions in the following list are examples of how we can approach implementation to produce equitable outcomes:

- Community members can:

- Negotiate explicit partnership agreements with funders, researchers and practitioners that support community members to:

- assess whether they are giving and receiving in ways that were expected and to change course when partnership agreements are not upheld;

- receive compensation for their contributions just as researchers and practitioners are compensated (that is, pay community members for time spent on implementation activities);

- play an integral role in implementation from start to finish—from defining need to assessing, selecting, and implementing interventions, including providing data, input and interpretation of findings that may inform prioritizing changes in implementation;

- Build capacity for continuous improvement by using data in feedback loops that increase the effectiveness of the intervention.

- Provide data and input on the intervention’s implementation and support researchers in interpreting findings that may inform prioritizing changes in implementation.

- Negotiate explicit partnership agreements with funders, researchers and practitioners that support community members to:

- Funders can:

- Be patient and know that quality implementation can take up to five years. Provide funding without the pressure to produce impact results before an intervention is fully implemented. Currently, only 12 percent of evidence-based programs and practices are sustained, because the rush to implement means failing to create the competencies, processes, and systems that embed the intervention into an organization or agency;

- Build capacities and provide technical assistance to community members in areas such as data use for continuous improvement and equitable practices;

- Know the difference between improved outcomes for some and equitable outcomes for all; and

- Enter as a partner promoting equal power and voice, not as a funder with privilege.

- Researchers can:

- Engage community members with openness to community experiences, knowledge, and history to learn how these complement your expertise;

- Build capacity for equity work by unpacking your assumptions and how they affect your work;

- Identify core components and adaptable components of the intervention you developed and validated;

- Develop technical assistance that considers and reflects cultural norms;

- Develop adaptations that incorporate the culture and background of participants; and

- Set yourselves up as co-learners in the implementation process and authentically value different ways of knowing.

- Practitioners can:

- Similar to researchers,

- engage community members with openness to community experiences, knowledge, and history to learn how these complement your approach;

- Build capacity for equity work by unpacking your assumptions and how they affect your work;

- Build capacity for data work. Ask yourself: What data are needed to understand how and whether an intervention is working?

- Build capacity to critically appraise and use research. Consider what ways the knowledge base can be relevant to your community and what else you need to know to implement in ways that promote equity.

- Similar to researchers,

Implementation science must make equity explicit to address disparities or else risk perpetuating or worsening them. Much of what we include in equitable implementation—for example, codesigned methods, participatory action research, and community-based research—has been developed and employed successfully in other disciplines. Now is the time for implementation science to embrace transdisciplinary approaches to advancing equity.