Getty Images

The immigration system at the southern border is a product of a century of conflicting policies aimed at facilitating trade, limiting undocumented immigration, and protecting national security. It was not designed to protect and promote the health and well-being of children and families, but it has an obligation to do so as a publicly-funded institution acting on the behalf of the American people. We all know that it is not meeting these obligations. When my colleagues and I visited the southern border, we did not just see a system that was ignoring the health and well-being needs of children and families. We saw a system that was intentionally causing harm and failing to meet the most basic obligations of a public system in a well-functioning democracy.

We all interact with systems every day. These systems, from public transit to health care, are governed by policies and protocols designed to further their mission and ensure the safety and well-being of the public. As part of my job working to promote child and family well-being through system reform, I spend a lot of time visiting child welfare systems across the country. These systems are intended to protect the safety, permanency, and well-being of children, and their ability to do so varies significantly depending on the policies and procedures they have in place. What we know is that in order for any system to function well, policies and procedures must ensure that the discretion used in decision-making is informed and not limitless, there is transparency to staff, families served, and the public, and there are effective accountability mechanisms in place to safeguard against harm, ensure a level of fairness, and promote well-being. In practical terms, this means that:

- staff who exercise discretion must have the information and tools they need to make the appropriate decisions, and operate within a framework that respects the rights and protects the well-being of the individuals involved;

- any policies and procedures in place must be made known, so that families, staff, and the community understand how decisions should be made and the framework within which the system operates to ensure a level of fairness; and,

- there are accountability mechanisms in place to ensure that any failures—both as a result of system functioning and individual decision-making—can be addressed and remedied.

These basic principles are critical to the functioning of all public systems, so that they can both accomplish their mission and maintain their legitimacy in a nation where institutions are expected to be accountable to the people and their representatives. When administrators and others responsible for the way a system functions ignore these principles, they place children and families in harm’s way. Our current immigration system at the southern border is doing just that. The consequences of this harmful system are not just being suffered in real-time as children and families are subject to unjust separation and inhumane living conditions, but they will be lasting, as families cope with the long-term effect of these traumas.

During our visit to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and surrounding areas in March 2019, my colleagues and I met with attorneys, temporary housing providers, volunteers, and clergy who work on a day-to-day basis with families who have recently crossed the border. We also toured two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) family detention facilities and observed court proceedings for unaccompanied children. Throughout our visit, we tried to understand the policies and processes that guided a family’s experience and interactions with the immigration system—both the formal, public, system as well as the informal system of private supports that has built up around it. This is what we found.

There is Near-Total Discretion

Families’ experiences with the immigration system at the border vary drastically and are entirely dependent on the discretion of those with whom they interact. One of the most critical decisions made on behalf of a family once they cross the border is whether they should be sent to detention after being processed by Customs and Border Protection (CBP), or released into the community. We learned that border patrol officers have almost unbridled discretion when making this decision. The language a family speaks, the way a border patrol officer asks a question or writes down the answer, and even an officer’s mood can all impact whether a family is sent to detention or released until their court date.

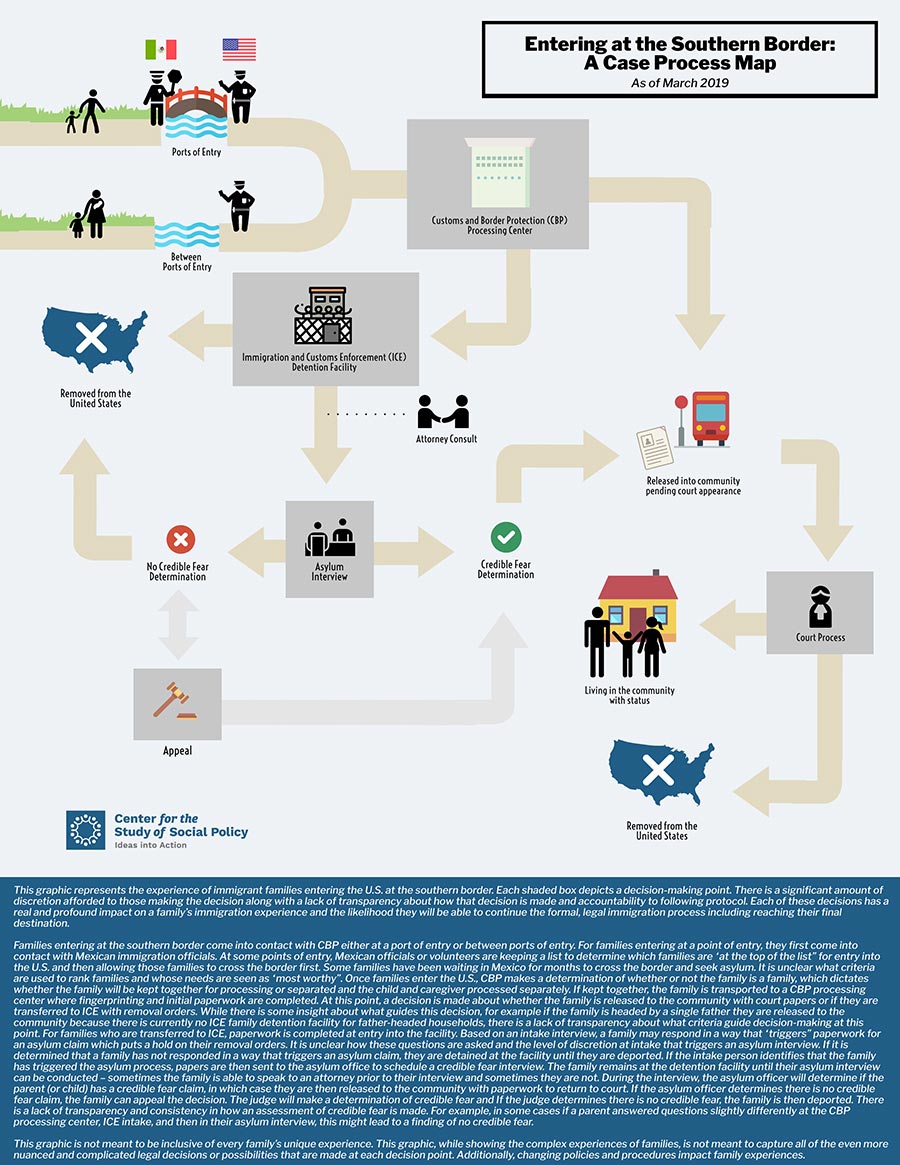

We attempted to identify guiding policy and protocols and to shed light on the experiences of families by creating a case process map to illustrate how families move through the immigration system at the border. Case process maps show how a person moves from point A to point B within a system and are built on policies and procedures designed to achieve a specific outcome. Ideally, they dictate what is supposed to happen each step of the way—including who should carry out each activity and the principles guiding these interactions. Importantly, systems use case process maps as a mechanism to remove discretion, promote transparency, and ensure accountability in decision-making. Given the amount of discretion at almost every decision-making point at the border, it was nearly impossible to understand the circumstances that would clearly dictate how a person would move through the system. The case process map we did create based on the information we received cannot fully capture the degree of variation and randomness separating different families’ experiences. It’s important to note that while this case process map represents what we found in March 2019 at the southern Texas border, what we know is that family experiences vary drastically depending on where they enter the country and the implementation of new policies, including the remain in Mexico policy.

While a certain amount of discretion is necessary so that every child and family is able to have their specific needs met, officials working with families need the skills and training to meaningfully assess family needs and make well-informed decisions. For example, in child welfare practice, the caseworker must use their training and expertise in child and family well-being to assess a family’s needs and connect them to appropriate interventions. Ideally, when a child welfare caseworker lacks expertise in an area they have resources available to them, including their supervisor and other experts, to help guide their decision-making so that it is informed by best practice. Further, in child welfare every decision made goes through multiple levels of review and sign-off, often including judicial oversight. On the other end of the spectrum, immigration officers not only lack training on child and family well-being, best practice, and trauma but also have near-total discretion over decisions with a life-altering impact on these families’ lives.

There is No Transparency

The immigration system at the border is notoriously opaque, which prevents staff, families, community-based providers, and the public from understanding the policies and protocols that guide how families experience the system. On our trip, we were denied access to the CBP processing facility where many families reportedly wait for days before either being sent to family detention facilities or released into the community. While we were allowed access to two ICE family detention facilities, we were unable to fully assess the policies and protocols governing decision-making in these facilities because they operate under waivers which are not publicly available. This lack of transparency makes it all but impossible for community-based providers to support families effectively once they are released from government custody.

Community-based and volunteer organizations in the Rio Grande Valley attempt to provide families with clothes, food, travel support, and other immediate necessities so that they can continue on to their final destinations and begin to heal. But these organizations are constantly functioning in crisis mode because they do not receive reliable information about how many families will be released from government custody on a given day, or the conditions and characteristics of those families. To the extent that they receive any information at all, it is through informal channels that may fall silent for long periods. This means that when there are a large number of families released within a day they may be forced to sleep on dirty cots, without sheets, in small rooms with 10 or more people. Because these community-based organizations have to operate largely by rumor, it is all but impossible to ensure they have adequate resources to serve families.

There is No Accountability

The rampant discretion and the lack of transparency make it almost impossible to hold the system, or any individual within it, accountable for the harms inflicted on children and families. For example, if a border patrol officer separates a parent from a child under suspicion that they are not legally related, the parent has no recourse. If a family does not receive adequate health care, food, or water in border patrol custody, there is no recourse. If a family is held in border patrol custody for longer than the legally allowed 72 hours, there is no recourse. In addition, there is no meaningful accountability process across institutions or between the community and the system. Without accountability, the harm caused to children and families through the violation of their rights and protections will continue.

People Can Change Systems

The immigration system does not have to traumatize families. People create and uphold systems. We need to establish policies and procedures to ensure that decision-making at the southern border is informed, transparent, and accountable, and meets the basic obligations of a public system in a working democracy. There is no reason a system should be able to operate without checks and balances that ensure integrity and fairness. Grounding our immigration system in these principles and best practices is the first step to building a system that is able to protect and promote the well-being of children and families.